India, but of whose imagination?

Introducing ourselves, and the drunk uncle of Indian history

The Indian past has never been more political. The Parallel Campaign is a fortnightly newsletter that questions the traditional (male, Hindu, dominant-caste, ‘secular’) orthodoxies presented in Indian schools’ history curricula. We investigate historical narratives by consulting sources and perspectives outside established media, and we review some of the most interesting academic books and articles currently languishing behind university paywalls.

There are no definitive answers here because we want to invite as many people as possible to an alternative conversation—on what it means ‘to do history’. If nothing else, we hope to convey that history matters, and to spark our readers’ interest in undertaking historical enquiries of their own.

“I give you my solemn word,” Ulrich said gravely, “that neither I nor anyone else knows what ‘the true’ anything is, but I can assure you that it is on the point of realization.”

Hello new friends!

Yesterday, we celebrated 73 years of the Indian nation awakening to life and to freedom. Our celebrations were more muted than they typically are, even though we’ve been faithfully shouting “go corona go” for months now. It feels somehow appropriate after another long year of calling each other ‘anti-nationals’ and trying to arrange visas to send people ‘back’ to our darling neighbour to the west.

It seems that we no longer – if we ever did – agree about what the nation is, or who has the freedom to count themselves a ‘national’. If citizenship were once a guarantee, it appears that it is no longer a robust enough one. Who is the “we” that made a tryst with destiny (and that the preceding paragraph refers to)? That midnight hour in August 1947, what “utterance” did the long-suppressed “soul of a nation” find? How long was it suppressed, and by whom? Where is that soul located?

The answers, of course, depend on whom you ask. You, reader, have your version. We, the people writing these words, have our own version. The Constituent Assembly had about as many versions as members. The point is simply this: there is no objective characteristic that marks the soul of this nation.

The nation is whatever and wherever it is imagined to be. History is critical to that imagination, and that’s where The Parallel Campaign comes in.

Who lives, who dies, and who tells your story

Benedict Anderson offers a useful starting point to convey what we are aiming to do with this newsletter. He formulated a general definition of ‘nation’ as an “imagined political community”. (We have a soft spot for Benny A and will almost certainly discuss his work and its critiques in more detail in later issues.)

This political community can be defined on the basis of certain characteristics, and ‘nationals’ are those who share those characteristics and are therefore part of that community. The characteristics could be anything: the nation can be imagined to consist of everyone who shares a religion, or a language, or occupies the same colonial administrative boundaries, or has blonde hair and blue eyes.

The nation is imagined because even the members of the smallest nation will never know all their fellow-members. Yet, they will think of them as being part of the same community, so long as they possess the relevant characteristics. Equally, if you don’t share those characteristics, then you’re not part of the shared imagination (and not a national).

Which characteristics are chosen to define the extent of the nation? And who chooses? This is typically when history is deployed in service of the nation.

In the same way that individuals are technically a reasonably arbitrary collection of cells that are constantly dying and being replaced, modern nations are a constantly changing collection of people dying and being born.

Individuals can think of themselves as ‘individuals’ because they imagine certain characteristics to transcend the lifespan of cells, and those characteristics are “who they are”. We rely on memory to identify and hold on to those characteristics. A person can think of themselves as a ‘dancer’, for instance, because they remember all the times that they have danced and loved it, and choose to identify themselves with those memories.

History is to nations what memory is to individuals. It offers – in theory – a coherent basis on which to imagine who is part of your community. Based on your understanding of history, you can assign importance to certain characteristics over others, and identify your imagined nation with those.

With both individuals and nations, the past furnishes a narrative that enables the whole to be greater than the sum of its parts.

That’s why it’s so important to pay attention to, and question, how and whose history gets told, by whom and to whom. The past may be a foreign country, but it has the power to deport people from the present.

The Parallel Campaign

The name of this newsletter is stolen from a favourite novel,The Man Without Qualities. In 1913 Vienna, the novel’s protagonist, rich and idle, learned and helpless, finds himself swept inexorably into the planning and execution of a grand and glorious patriotic celebration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire —the spectacle of the century. The mood is triumphant, the salons of the famous and powerful are awash with money, and the state is resolved to put on a show that no one will ever forget—but they lack a unifying Idea. A theme, a narrative, a word to capture this historic moment and the essence of the Empire. The Parallel Campaign is launched—and the novel’s thousand pages endeavour heroically (and hilariously) — to find the Idea. An idea that invokes tradition, power, and a shared past.

Then the Great War comes, as you knew it would, and an entire world is swept away forever.

Sounds a little bit familiar, yes?

We decided to use the idea of The Parallel Campaign to explore why any single, unifying narrative of national history—no matter how empowering or comforting it may seem—depraves us all, and dooms us to fail at resolving the hatreds and divisions that plague us.

We want to ask: what is a historical feeling? What is our historical feeling? In her wonderful recent book, Aparna Vaidik defines history as a kind of strange darshan—a privileged witnessing, a celestial viewing of the supreme form of the world, the great chain of events. Open, by definition, only to a few.

We presume to go a little further: in our view Indian history as it is commonly understood by the country’s citizens and political elites – and importantly, ‘Mainstream History’ as it is taught in schools – is not just a darshan, but a puja, a performance full of its own pieties.

The analogy is intentional, because the people who are entitled to perform pujas and history are often the same, and these tend to be even fewer than those who get to do darshan.

The monster we particularly hope to slay is something we like to call the politics of positivism. In India, this has led to a situation in which we might define Mainstream History as a kind of applied science of hurt feelings and public sentiment.

On the one hand, there is a desire to never forget the dead, or to lose the power of their example and their sacrifice. These are, whatever their other merits or demerits, subjective things. Whether someone is a refugee or an invader, whether commiting jauhar is an honourable sacrifice or to be the victim of an oppressive, misogynist system, depends on whom you ask, which sources they consulted and how they interpreted the sources through the prism of their own biases.

Yet, on the other hand, this mainstream version of history stubbornly holds itself out as ‘objective’. Under the veneer of social-scientific validation, like a drunk mansplaining uncle spoiling for drama at a boring shaadi, it flexes its muscles as an Authority that will tell you What Really Happened.

We end up with something that sounds an awful lot like: “This ‘fact’ is proved absolutely, irrefutably true, because it makes me feel the way I want to feel, which is that I am respectful, rational, objective, and vindicated.”

This fortnightly newsletter is a challenge to History Uncle’s positivist stranglehold on the nation.

In each issue, we will take on a particular aspect of contemporary politics or culture – say, replacing Urdu with Sanskrit in railway signs, or love jihad – and examine the dominant historical narratives that underlie it.

We want to show how history is ‘made’, and to understand the biases and predispositions that may have led to any one version becoming predominant. Of course, no one (least of all us) is free of bias and there is arguably no such thing as an un-self-interested historical exploration - often, what leads us to look to the past is a vindication of our own place in the present.

We will try to be as self-aware of this as we can, but we will link to all our sources (and try to find non-paywall versions) so that you can read them and come to your own conclusions. If you disagree with, or want to add to, what we’ve said – send us a letter! We’re always on the lookout for letters to publish, so long as they have a credible historical basis and aren’t vituperative. Be nice, people.

Who are we?

Given everything we’ve just said about the importance of who tells stories, here’s a little bit about us.

We are two friends of long association: one of us is studying to be a professional historian, and one of us is an amateur, a former undergraduate historian who now works in law and policy. We are young, upper-middle-class, dominant-caste women from a big Indian metropolis – probably replete with all the biases those things suggest.

We are both Tommy Macaulay’s bastard children, and speak English as our first language. Between us, we can just about get by in Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati, and Farsi (and French and Marathi on good days) – which will impact which sources we can reliably turn to – but our English-speaking political reality will no doubt have a bearing upon our interpretation of any sources.

It’s good to meet you! We’ll be back in your inbox two weeks’ time.

Postscript

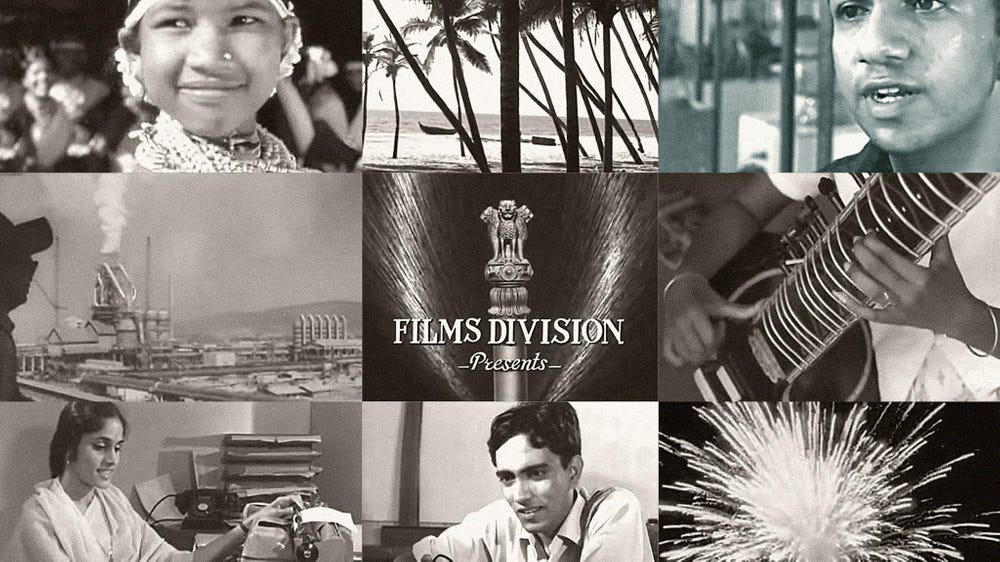

'I am 20' is a 1967 video from the state-run Films Division, which interviewed 20-year-olds, all born in or around 1947, about what they thought of their country (IITians, as ever, are overrepresented).

In 2015, Midnight’s grown-ups told the story of a filmmaker who set out to find those same people to ask them what they made of India almost 50 years later.

We found ourselves watching the video for the umpteenth time to mark Independence Day, feeling a familiar pull of identification and disavowal, and stirrings of the learned helplessness that the film’s protagonists confessed when they were interviewed again. It was a reminder that history is never as neat or linear or conclusive as we think it: everything and nothing, always and never, changes. On the flipside, it’s probably harder to get into IIT, but at least there are more women there now.

There always have been parallel campaigns

This one is accessable

Brilliant. Nice to see a young thinking duo. Mubarak gals